Lesson plan: Get Down On the Ground

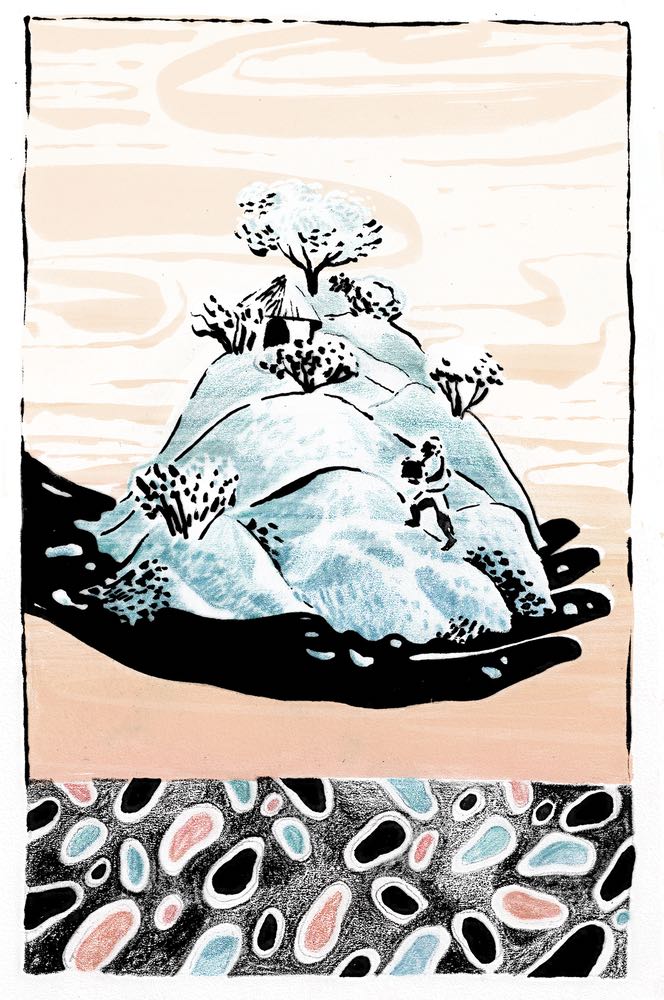

We tend to avoid the ground. It’s fine to walk on and maybe to dig with a shovel, but most people who are not farmers avoid contact with the soils that sustain all the grass, trees, and other plants all around us. While in Unit 1 we took a more removed eye to assessing soil’s textures and components, now it’s time to use the other senses as well. What does the smell or even taste of soil evoke for you?

One of the members of our seminar had this experience: I was on the ground playing with my child when I smelled something deeply familiar. It was the soil, which I had known when I was her age. Time and the growth of my body had distanced me from interacting with soil, its texture, its smell, all of its properties, as intimately as I once did.

Understanding soil in all the ways expressed in this syllabus must begin with the stuff itself. It’s not an idea–it’s a substance made up of living and non-living things. The first assignment is to smell it, taste it, and feel it wherever you live.

Some examples of what engaging with soil in this way might evoke:

The artist Laura Parker suggests tasting soil and created an interactive-installation called Taste of Place in which she held soil tastings with samples from eighty-six farms. Taste your soils and write a paragraph about the experience.

Or, read the first two pages of The Known World here to consider the tangled ways tasting soil can evoke a lifetime of accrued knowledge of a place.

Here is another article that helps reconnect with what it is like to dig in the dirt:

Emma Marris, “Tending Soil,” Emergence Magazine

Assignment 2: Soils and Home

How does soil type help to define your place in the world? It’s a strange question because you probably had no idea what your local soil is called or what it’s made of but it certainly has played a role in what makes up the ecology of your region.

Take a look at the World Soil Explorer, which allows you to see soil types in any country, city, and even locality. If you live in the United States, you can look up your state’s official soil: the soil most common in your state.

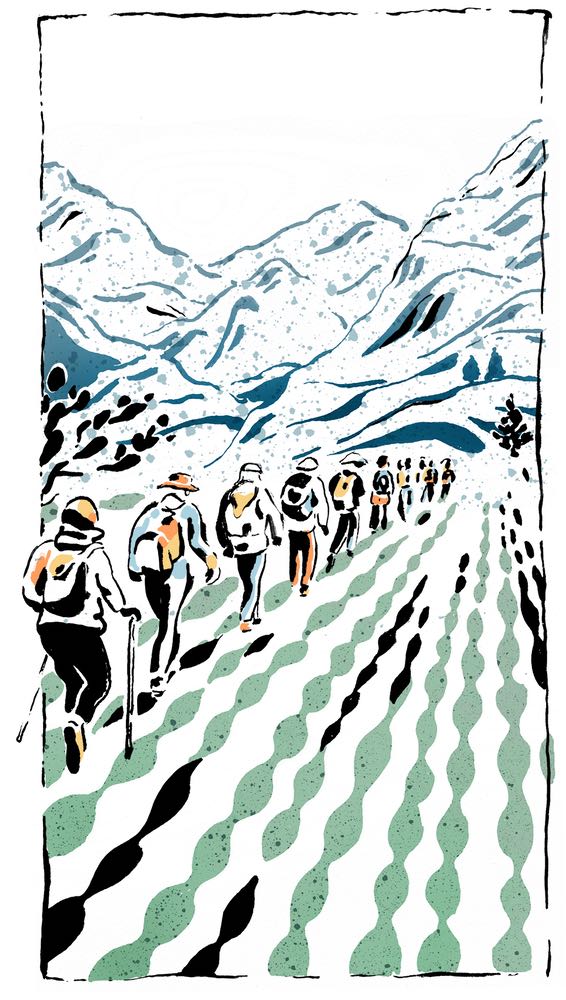

The American naturalist and philosopher Henry David Thoreau engaged in a kind of experiment in 1845. He built a very small house and lived on the shore of Walden Pond for two years, two months, and two days. In Walden, Thoreau writes about the entire environment of the pond. One of the things he did in those years was to grow acres of beans for himself and to exchange for other locally-grown products.

Read the first few pages of “The Beanfield” from Walden. How does cultivating the soil’s of Concord, Massachusetts, deepen Thoreau’s relationship to his native town? Where would you live to be close to your soils and how do you think the experience would change you?

Where would you live to be close to your soils and how do you think the experience would change you?